I do have a computer science MSc having studied IT as joint major as an undergraduate, but it was human-centred design orientated so I find diagrams a great way of understanding technology architecture – particularly as a system or ecosystem even. I mention this because Matthew Parris at GE Appliances has provided feedback on my LinkedIn announcement about the reboot of this blog (see here). It was in response to my earlier post about ‘interoperability’ that featured his diagram (see here). Short version is his feedback pointed out the limitations of traditional stacked or tiered hour-glass architecture (see here and here), and that ‘Unified Namespace’ is a more scalable and modern way of architecting industrial data system:

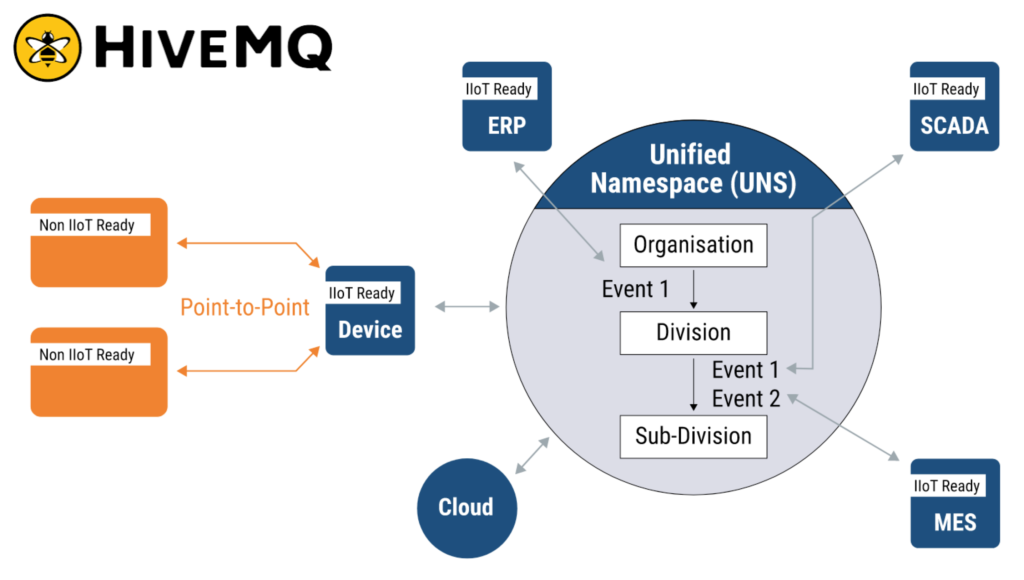

Main takeaway: Unified Namespace is a single source of truth for the current state of the business. It’s closer to hub-spoke model, rather than a linear model of the hourglass figure.

Matthew also kindly recommended this article on What is Unified Namespace (UNS) and Why Does it Matter? by Kudzai Manditereza at HiveMQ. And also one by Paul DeBeasi at Gartner on Reference Architecture for Integrating OT and Modern IT that is sadly behind a paywall.

As an aside, I think the UNS concept could do with the kind ‘in a nutshell’ explanations that Gennaro Cuofano offers on his 4 Week MBA I mentioned here. Just saying. However, I think the following from Kudzai gets to the nub of the problem that Unified Namespace helps solve:

To address the failures of traditional industrial data architecture, you need to shift to a paradigm that draws from a modern distributed architecture. Instead of having data exist in silos within and across layers of your technology stack, you make it accessible in a unified way, such that it appears as if it’s all in one place. This enables all your enterprise systems to have one centralised location to get the data they need for what they want to accomplish.

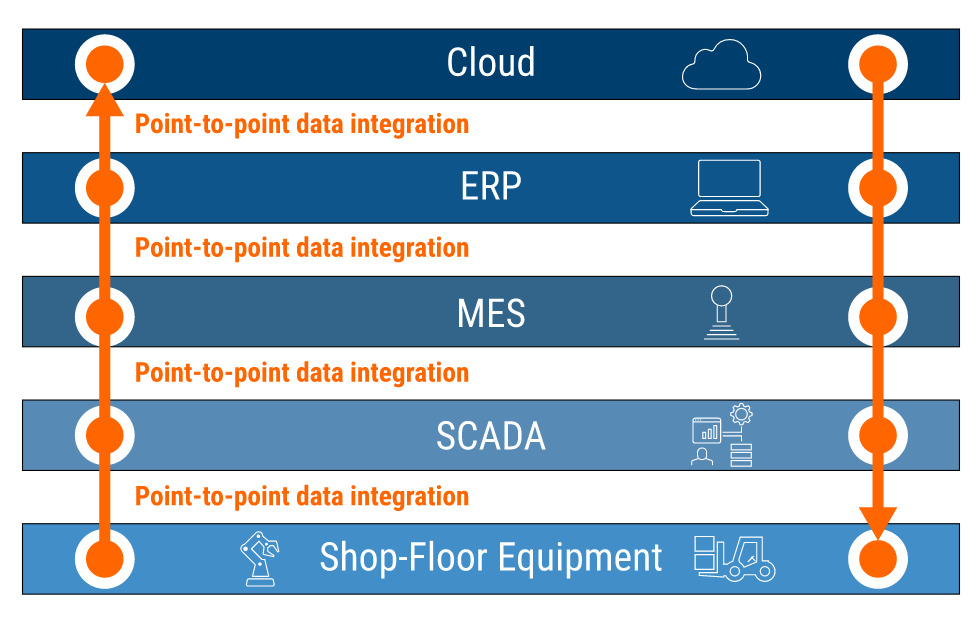

Or put another way, UNS is the antidote for the ‘Disadvantages of Traditional Industrial Architecture’ as highlighted in this diagram he shared showing the ‘data movement in a traditional industrial architecture’ and explanation below:

Most existing industrial systems model traditional pyramidal network-and-system architectural structure (the ISA 95 functional model). As depicted below, this architectural approach is characterised by a technology stack that includes factory-floor components at the bottom and enterprise/cloud components at the top. Within this stack, each layer is connected and only communicates to a layer that is directly above or below. So, data moves up or down one layer at a time using point-to-point connections. While this data architecture served its purpose in the mid to late 1990s with the introduction of PC-based control and enterprise integration, companies are taking big risks by blindly adopting it as the foundation for their digital transformation strategy. Unsighted endorsement often leads to unfulfilled promises, and many digital transformation efforts fail.

This is starting to dive into the weeds a bit more than I usually go into on here because as explained to control systems specialist Edward Williams at Thanium Nine, the backdrop to this blog and possibly its purpose is based on the following observations I have written about in Smart Buildings Magazine:

It is worth noting that the drivers for creating and justifying a smart building, whether for retrofit or new build, have changed significantly in recent years. A decade or two ago most Smart Building initiatives were driven from the bottom up by technology manufactures, engineers and building contractors. They provided building environmental systems to address the needs of the building and those maintaining them.

The emphasis now for Smart Building realisation is to adopt a top down approach where the needs of building occupants is the starting point. Their requirements and expectations have placed ever increasing challenges on work space designers and technology providers. It follows that there are now many more stakeholders involved and the whole journey to Smart has become much more complex as a result.

That creates an emerging disconnect around communication and understanding between some of the many parties involved in the whole process. Exploring these shortcomings further could feed into helping create a common understanding between all stakeholders from which a set of accepted principles, frameworks and best practice guides could be compiled.

Smart Buildings Magazine: Retrofitting buildings and the drive towards net zero (15th May, 2023)

Building users and facilities staff remain frustrated by the lack of influence and input they have over smart specifications defined during the design and planning phases, by stakeholders that will walk away at practical completion, even though they ultimately run the building. A proxy for that tension was captured by Giovanna Jagger, global market development director at the IWBI who raised the distinction between ‘efficient’ and ‘effective’ buildings. Her point being that technology and materials can be specified and deployed to make buildings more efficient (e.g. for energy consumption), but if they are not occupied they are not effective and therefore not sustainable.

Smart Buildings Magazine: Navigating the perfect storm: how strategies for future proofing retrofits need more integrated and joined up thinking (30th August, 2023)

Put another way, what I am really trying to do with this blog is help facilitate common understanding between different stakeholder groups that can often seem like either side of a dichotomy, e.g. top vs bottom up, AEC industries vs Operations, those more tech-first trying to make buildings more efficient vs those more people-first trying to make buildings and workspaces more effective, and so on. And part of doing that is by trying to provide more jargon free translations along with diagrams to help improve understanding and drive adoption.

My point being that what Matthew has highlighted and what Kudzai explains is an important perspective – hence highlighting it here. And it is one that strikes me that is worthy of debate by a community like the one James Dice facilitates at Nexus Labs and others where mechanical electrical and networking engineers gather. And possibly also CIBSE‘s Intelligent Buildings Group and similar committees at other relevant trade bodies and likes of Geoff Archenhold‘s Smart Buildings & Sustainability Forum. I think could help with the translation from the bottom-up to the top-down, and particularly if there is some consensus.

But as mentioned to Ryan Casey at Cisco as part of the extended discussion about ‘interoperability’ and ‘Unified Namespace,’ there seems to be a tendency for those coming at this from the bottom-up to be evangelical and sometimes zealotry about technology architecture design philosophies. So much so that I think they should be another layer to the 3 types of MSI that James Dice has written about, and that’s how those involved at the (master) systems integration coal face could also be bucketed into 2 groups:

- Pragmatic MSI: often more liberal approach that bases solutions on the realities on the ground including client needs, budgetry constraints, time frames and so on – particularly when it comes to retrofitting.

- Idealistic MSI: often zeolotory/fundementalist or at least evangelical about their preferred tech architecture design ‘philosophy’ being right – despite the onward march of technology.

That dichtomy is possibly a reflection of what is happening on a broader level in society. But in this space I have noticed that when I probe a that fundamentalism/evangelicalism/zealotory by scracthing beneath the surface and particularly by speaking to others, then I find that invariably it is usually linked to the business model of its advocates, e.g. being a VAR of a particular technology or having a reseller agreement and/or some kind of alliance (either strategic or informal). Greater transparency is one remedy for assessing neutrality particularly when it comes to specification. But I also think the kind of more open debate I have suggested above can help with educating the market.

Part of the reason for mentioning all this is I’m interested to know if and how there could be some kind of minimum viable technological foundation for smart enablement that could be built upon and scaled, particularly in retrofit scenarios. And if there is some consensus about the architecture/design philosophy of that. This would need to include the commercial realities including cost of technology. But also those linked to any potential skills gap when it comes to deployment and management of that foundation or whatever best describes a ‘modern distributed architecture.’ Maybe that’s one for another round table.