Back in the mid-aughts, I hosted a podcast series as a follow-up to the Connecting Marketing book I co-wrote with Dr Paul Marsden. One of the themes I explored was ‘brand storytelling’ and that included speaking to Annette Simmons, author of Whoever Tells the Best Story Wins, The Story Factor and growing list of other titles along similar lines (listen to Episode 1 and Episode 2).

I also spoke to Greg Galle who back then ran C2 LLC in San Francisco and helped (mostly tech) brands define and better communicate their stories (listen Episode 1 and Episode 2). C2 had just released their ‘The Story Book’ guide on ‘how to succeed at competing.’ It gave some guidance about telling those stories that win, which starts with asking 3 deceptively simple questions:

- Who are we?

- What do we do?

- Why does it matter?

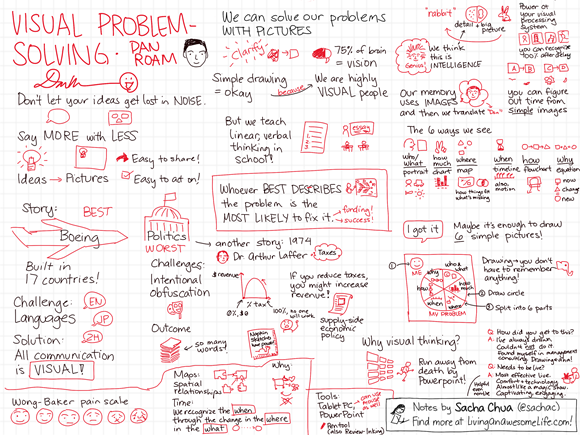

It’s interesting to see how answers to those questions are rarely aligned when asked across an organisation and also of its clients and partners. That’s one for another post, but linked to the better telling of stories is the following quote by visual storyteller and best selling author Dan Roam:

Whoever best describes the problem is the most likely to fix it.

Sacha Chua (2013): Sketchnotes: Visual Problem-solving–Dan Roam (DAN ROAM!)

I mention this because I see a lot of very polished infographics, some of which I am sharing on here. But as Dan points out, it is not how well your visual storytelling is executed but more about how well you describe the problem you help solve, i.e. the jobs-to-be done, pains relieved and gains improved (see more on this here).

From what I have seen, that ‘positioning’ is far too often missing from those selling smart building solutions, which is not currently being helped by the various accredited solution programmes out there. Without pointing fingers, in some instances these are little more than a self-certifying exercise via form filling to show if and how a solution/service helps accrue points on a framework (in theory).

Matthew Marson at JLL Technologies recently wrote about a related problem as part of his column for Smart Buildings Magazine by asking if the industry has an honesty problem:

Firstly, there’s those that use the ambiguity of the latest buzzword to allow a buyer to read what they want into the capabilities of a solution. “It uses big data”. You mean, it captures all the data points over time? Seems reasonable and not noteworthy. “It has data analytics”. You mean that you’re able to visualise all the points on the BMS? Oh, like it always has been able to? For many working in the controls world, new technologies that are able to decipher long points-lists and automate commissioning represent a risk to business. Controls folk seem to be rebadging the same old stuff they’ve been doing for years to give an appearance of having the latest capabilities, or simply to lock out potential new players.

The second type is those that simply don’t tell the truth. Speaking with an industry peer, they shared their role in supporting a client in selecting some technology for a new scheme. After informing a vendor, who’d been through a competitive tender process, that they’d won, the vendor asked to modify their proposal. It turns out that the technology they were selling, is, in fact, “on the roadmap”. That’s technology speak for “we haven’t created it yet”. Not only did it not exist, but there was no guarantee that it would exist within 12 months. In the same way that my qualifications in brain surgery are “on the roadmap”, I today, am unable to perform lobotomies. Seems those leading at some companies have already experienced my medical skills.

Accredited solution programmes may inadvertently encourage that problem because of the way that can be gamed through self-certifying particularly by those that may help solve important problems but don’t score highly in the framework for doing so. Or because they are simply over claiming the capabilities of their platforms/having the truth problem highlighted by Matthew above.

That’s also because the real value to those solution and service providers is often simply the visibility they get from demand-side by paying for the accreditation, rather than necessarily helping those end-clients better understand the promise-gap between what is claimed and what’s actually delivered, e.g. by assessing that as part of the accreditation.

The framework collaboration I am proposing that is akin to Scott Brinker’s ‘Marketing Technology Landscape Supergraphic’ may not solve the honesty problem highlighted by Matthew, but hopefully it might help get some consensus about the real problems that need solving as a starting place, i.e. as a way of categorising those solutions (see more here).